Generated by Adobe Firefly AI

Where do I start? This is going to be a post sharing my personal journey and the first-hand experiences I had supporting a blended learning initiative.

I was heavily involved in the first rollout of Blended Learning 2.0 @NUS. It was challenging because everyone had a different understanding of what blended learning was.

In general, blended learning is the meaningful integration of asynchronous (online) and synchronous (in-person or online) interactions. Because it should be meaningful, there is no one-size-fit-all — the course design and type of interactions differ from course to course depending on the subject, learning objectives, assessments, timing, audience and so on.

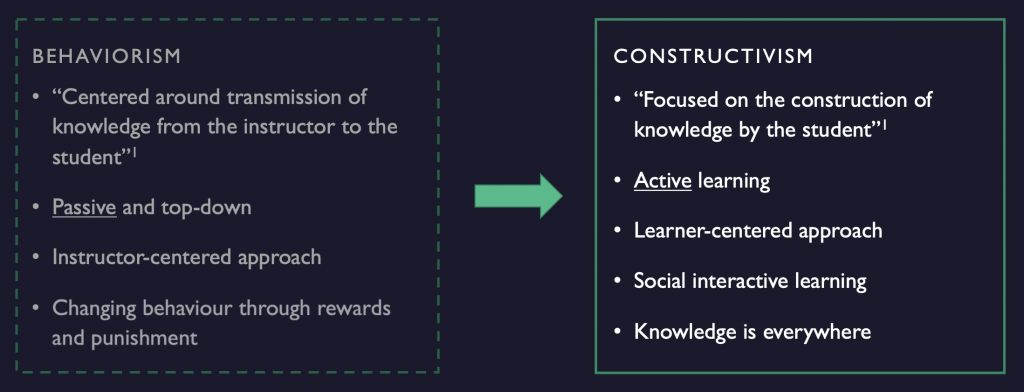

However in large-scale top-down implementations, the management had to come up with institutional frameworks and guidelines for the faculty members to know if they were doing “Blended Learning of Your Institution”, not just any type of blended learning. Most of the faculty members felt they were already doing blended learning in general because of the pandemic. The suggested guidelines may be helpful for those who are new to blended learning, but some may not agree with the given definitions as they know best what works for their students. Those who were early adopters of blended learning would done many iterations over the years to improve the teaching, cognitive and social presence outlined in the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework, whether knowingly or unknowingly.

There are many benefits to blended learning as mentioned in this Guide to Blended Learning, but unfortunately, some instructors have realised that university students are not self-directed in their learning and instead of adopting better blended learning strategies, they prefer reverting to traditional in-person lectures (without any recording) after the pandemic. They also do not see value in spending time and effort pre-recording didactic contents for the students’ learning at their own pace. In my view, this is forfeiting the majority of the students who are self-directed learners and are keen to review the videos again to familiarise difficult concepts, or to revise during the exams. Everyone learn at a different pace, even take down notes at a different pace.

So how can we design more engaging and meaningful learning activities in the online environment?

Pedagogy: Much of the CoI had been discussed in this ONL course so I shall skip reiterating the concepts. Fiock provided a comprehensive list of instructional activities that are practical and helpful for improving each CoI presences — pick and choose as you deem fit!

Technology: Leveraging on the affordances of technology and choosing the suitable tools can help to overcome physical limitations and support your implementation of both the synchronous and asynchronous activities effectively. It’s helpful to have some imagination about the virtual world and space that characters (students) are in.

Pedagogy and technology are tightly integrated — sometimes, technological developments influence the way we design our courses and assessments. A good example is the latest hot topic on generative AI. It forces us to rethink how it augments in a blended learning environment. It’d helpful to have some imagination of the online learning space as a virtual imaginative world — how these story characters (your students) may use various mediums to communicate with each other and with you.

In a poll by EduCause, 83% of the respondents agree that “Generative AI will profoundly change higher education in the next three to five years.” It is interesting to note that this issue is big enough that middle and senior management in educational technology units are tasked to look into the AI capabilities and guidelines for the faculty’s appropriate use of generative AI for teaching and learning.

“The “technopositive” among us may simply be quicker to use and look for the benefits of new technologies.” – Mark McCormack

This may be challenging but we simply cannot run away from using technology or from the existence of today’s virtual world. So we might as well embrace it and try out some of these tech tools and instructional strategies to see how it transforms your students’ learning!

References: