Growing up a few decades ago, playing with Lego meant play, imagination, innovation and craft, somewhat different to what it means today. It was all about squares, rectangles, twos, sixes and eights, and whoever had the platforms and wheels could build the most imaginative campervans ever dreamt of! Nails and teeth were indispensable for getting sticky small parts separated, as was imagination to form a more-or-less 3D representation of the imagined. Characters all looked pretty stock-standard and who can forget mom’s annoyed shouting when the toothpaste lid was still the bucket in the campervan?

80s Legos

80s Legos

Legos today look and feel different. Sure, the sixes and twos, the platforms and wheels are still there. But the games have evolved. We find kids playing Lego girls where they dress, accessorize and swap outfits, helmets and feet. In our house, an entire box was dedicated just to the characters! Using the mechanical Lego they build pulleys and levers, ramps and lifts. Toothpaste lids have been replaced by actual tiny buckets, laptops, phones and iPods, and dragons actually look like dragons once all the pieces have been assembled correctly. Not to talk about Lego electronics, coding and robotics integrated in play.

2020s Lego Characters (Unsplash)

2020s Lego Characters (Unsplash)

Lego Robotics (Flickr)

Lego Robotics (Flickr)

As play with Lego has evolved, so to have the skills, knowledge and competencies needed to engage with these toys. Imagination once used to build intricate 3D structures, has evolved beyond mechanical gears and pulleys to coding the robotic characters from a laptop or tablet. Children being play-orientated, seem to have easily adapted and dexterous fingers and ideas have followed suit. Teachers then appropriated play, structuring it and making it purposeful, adding play constructs to curriculums and identified literacies that should go along with such serious play.

The same evolution of knowledge, skills and concept seem to have happened in the digital world. Similar to the block building of Lego, Roblox and Minecraft engages children from a young age in virtual building and imaginative play. Of course the goal is coding and developing appropriate literacies and competencies through serious play. But ever-vigilant entrepreneurs soon realized the appeal of making such serious-play events curriculum friendly and sold these as goals for development.

Imaginative play for the sake of playing develops capacities to innovate and create with whatever tools and instruments are available. With a couple of block and a platform, or mining areas and a pick axe, the imagination can summon any number of structures, characters or fantasy worlds. In the vastly digital world we work and play in, space to image, innovate and create is often at a premium. Very often attempts to categorize and order lead to measurable goals, clearly defined objectives and lists of literacies that need to be developed. This commentary is not intentionally critical of lists and categories, despite appearances. It intended as a reflection on the loss of playfulness or conversely the use of purposeful, serious play to develop such lists of skills and competencies.

David White’s matrix using the continuum between the visitor and resident applications of digital affordances, bring this tendency to list and categorize to the discussion. Our weekly PBL meetings raised the question: ‘what is the ideal’ of a digital map? The resident and visitor labels also raised questions. Are these terms appropriate or can we think beyond them?

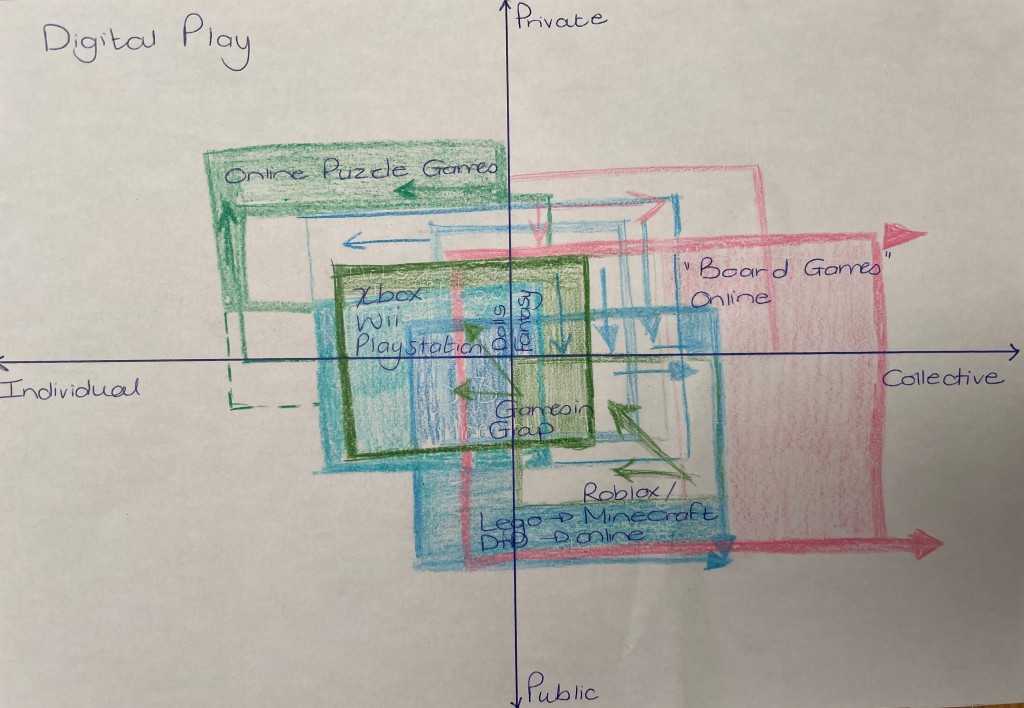

Contemplating these questions, I thought beyond digital to play. How has play changed from non-digital to digital? How has this affected the digital literacies required to play? To start off, I first mapped play to White’s matrix. However, the visitor and resident zones didn’t work for this. I changed these with Individual and Collective. Then I looked at Personal vs Institutional, which again didn’t quite work. I changed it to Private to indicate play in private, personal spaces, and Public to indicate play in spaces where one can be seen by an wider audience.

A play map emerged based predominantly on children and adults’ play in South Africa, and in my middle-class contexts (see below). The concept of play here excludes ‘serious’ play like players in a sports match, playing of instruments (like piano) or play in terms of gambling or high-stake card games. It also excludes play as a form of therapy.

A Play Map

A Play Map

The map shows that play in this context moves easily between individual and collective spaces, and between private and public spaces. Board games are almost always played in community, whereas Puzzle-type games are mostly payed individually but can also be played with others as when a family builds a puzzle togethers. Lego transfers from individual private play to collective private play, with for example individuals or groups playing Lego at home. However, as discussed above, Lego can also be played in more public spaces by individuals or groups – students building Lego structures at school or at electronics or robotics clubs for instance.

Play over the past few decades morphed into digital spaces, and players have had to adapt and flexibly move to the different zones where play takes place. I thought of board games for instance, Catan or Monopoly, not to forget Scrabble and Risk! In a digital world, the need to beg siblings or friends to play board games is vastly reduced by large online games where one is able to play against any number of players scattered around the world. Board games have thus become more collective and public, moving from traditionally private spaces. Whether this move carries as much joy and engagement, is open to debate.

Moving in opposite ways, traditional outdoor games like hide-and-seek, rope jumping (with others), dancing or even some serious sports games, have morphed to VR goggle-wearing console-driven spaces, evolving beyond XBox Connect or WII games. Of course such virtual games can be played in public spaces, but these have also moved away from the public to private lounges, living rooms and such like, Lego-type play has also evolved. Many of the elements from Lego has been duplicated in games like Roblox or Minecraft, moving to more public and less private spaces. Even playing with dolls, drawing or painting has moved online, with virtual drawing, Royal High, Simms, etc. In many instances, the once private world of fantasy doll-play or drawing, has become more public, playing with others from anywhere in the world. Even playing with one’s pets has become digitized with players able to swop out pets with many others around the world, while they nurture and care for pets, and upgrade them with all kinds of accessories.

Many digital literacies developed to accompany the move from non-digital play to play with emerging technologies. Digital literacies developed to search for and evaluate source material, finding the latest game rules and plays for instance. Engaging in online forums to strategize, discuss and collectively act required literacies to collaborate and communicate online, while learning to distinguish between trolls and hoaxers, bots and genuine engaged players added further nuances to this. I vividly remember the hearth ache when a niece’s favourite online neon rainbow unicorn was stolen by some unscrupulous villain, or the indignation of having no return-swap of digital doll-clothes when she had sent her favourite dancing-shoes accessory in good faith. Digital literacies developed through tears and now she is hyper-aware of trolls masquerading as innocents.

Play research has over many decades shown the immense potential of play to develop imagination, creativity and innovation, resilience, flexibility and originality of thought. Play has morphed, and so have the need to learn digital literacies in spaces where many teachers and parents rarely venture. Perhaps a greater engagement in digital play would mean less list-making off all the digital literacies we need to teach and more purposeful inclusion of play and game-based learning to develop such through play.