I would count myself lucky to be with ONL PBL Group 5 because our group definitely embodies the spirit of sharing and openness. I have learnt a lot from the group members, from the discussions to the tools and techniques that the team use.

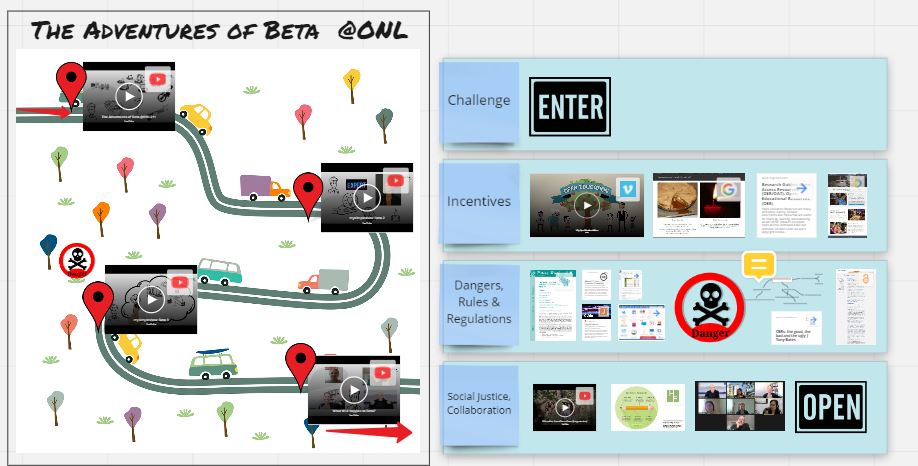

For example, in the presentation of Topic 2 on Open Learning, we have used SimpleShow to create the storyline and Miro board to present the story. You can check out our work here.

https://miro.com/app/board/o9J_lNlNVVQ=/

The topic of open learning is relatively new to me, as it is not a regular topic for discussion in my context. In Singapore, education is free and compulsory (MOE) for at least 10 years, for any child aged 7 onwards. Even for those who cannot afford post-secondary education, there are abundant opportunities for application of study aids and bursaries. For working adults, the government heavily subsidies skills-based training via the SkillsFuture Movement, and corporate organisations are incentivised to provide training their staff via various schemes. Indeed, Institutes of Higher Learning (IHLs) have provided free content in the form of Learning Days, free talks, webinars, seminars and workshops from time to time. As such there is no lack of content and opportunities for anyone who wishes to learn. In this environment where access to education is encouraged, the concept of social justice (Hodgkinson-Williams & Trotter, 2018) and reason for open education seems to be less urgent.

Besides, curriculum in Singapore is highly regulated by MOE (Ministry of Education) for PET (pre-employment training). For CET (continuing education training), the SkillsFuture Singapore (SSG) plays a strong role in providing Industry Transformation Maps and Skills Frameworks to guide organisations, individuals and training providers in emerging skills required by the country. As such open education will pose challenges on decision making on curriculum, content and relevant knowledge sets in such settings.

There is no lack of ‘free content’ available on the internet. With over 90% of households in Singapore having internet and broadband access (IMDA), access to global educational resources is easy. However, such content is usually perceived as ‘informal learning’ and not recognised as formal credentials and certifications. Sometimes, educational content are created free by organisations not for ‘social justice’ reasons but for personal gains. Reasons such as positioning themselves as thought leaders or encouraging industry usage of their products are prevalent. Some examples are Google Analytics, Facebook Blueprint, and AWS Academy where educational resources are freely available, but the corporates are also the biggest winners.

While open and free sharing content is beneficial for those who are unable to pay for it, it is on the goodwill and onus of the content creator to constantly update and keep the content relevant. As such, we sometimes find free but outdated (and potentially misleading) content on the internet. This may affects learning eventually since students’ prior knowledge influences their learning of new knowledge (Ambrose et. al., 2010). When something is paid, there is a responsibility and accountability on the content and experience provided, not to mention sustainability for the content creator to continue to create and update new content.

Nevertheless, for educators, some form of sharing and openness in education resources can be useful in the sense that we do not need to ‘reinvent the wheel’ each time. Costs can also be kept low. Cross-sharing of content also optimises the amount of time educators spend on content creation and frees them to spend more quality time in students’ interactions. In a Google Analytics class, my student shares that she has already learnt the topics we spoke about, from the internet because resources are readily and freely available. “I watch all the videos, and I already know the ‘hows’,” she says, “…but I never know the ‘whys’ until I come to your class”. In my opinion, the real value that educators bring, is not content but knowledge, insights and experience to help students connect the dots and teach them how to fit the pieces of content into a jigsaw.

Hodgkinson-Williams & Trotter (2018) advocates integrating and combining different forms of educational materials, sometimes from open resources and sometimes from local teachers. This requires integration and pedagogically sound practices where teachers access a wide variety of resources available and hand-picked those most relevant to their students, and curate them in a customised package. However, copyright restrictions could be difficult to understand and manoeuvre, especially in cases where educators are employees and their work belong to their organisation. The lines between ‘fair use’ and privacy are also blurred, and educators may not be in the best position of deciding whether their work can be shared or not, and in cases where it is created jointly with colleagues, whether they have the rights to openly circulate the content.

In an ideal world where resources can be shared and curated by artificial intelligence, human intelligence can be freed to provide more value-added interactions and experiences for the learners. But before that, the issues of trust and copyrights need to be resolved.

REFERENCES

MOE (Ministry of Education)

https://www.moe.gov.sg/primary/compulsory-education

IMDA (Infocomm Media Development Authority)

https://www.imda.gov.sg/infocomm-media-landscape/research-and-statistics/infocomm-usage-households-and-individuals

SSG (SkillsFuture Singapore)

https://www.skillsfuture.gov.sg/skills-framework

Hodgkinson-Williams, C. & Trotter, H. (2018). Social Justice Framework for Understanding Open Educational Resources and Practices In the Global South.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332468165_A_Social_Justice_Framework_for_Understanding_Open_Educational_Resources_and_Practices_in_the_Global_South/link/5cb72cd9299bf120976b0d00/download

Ambrose, S.A., Bridges, M.W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M.C., Norman, M.K., Mayer, R.E. (2010). How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching.

https://www.wiley.com/en-sg/How+Learning+Works%3A+Seven+Research+Based+Principles+for+Smart+Teaching-p-9780470484104

Google Analytics Academy

https://analytics.google.com/analytics/academy/

Facebook Blueprint

https://www.facebook.com/business/learn

AWS Academy

https://aws.amazon.com/training/awsacademy/