Echoes of a “Gen X” childhood

I grew up at the end of the non-digital age (if a label was needed, Gen X would probably be nearest the mark). In my childhood, I remember my parents buying the first desktop computer for our home running on Windows 3.11 and we had to use a dial-up modem that made a loud, distinctive screeching noise every time we wanted to connect to the internet. I also remember getting my first mobile phone when I was 15—it was a Nokia 3310 and I could only make phone calls, send text messages (limited to 160 characters) and play a game on it where an increasingly long snake tried to eat little digital apples without running into itself.

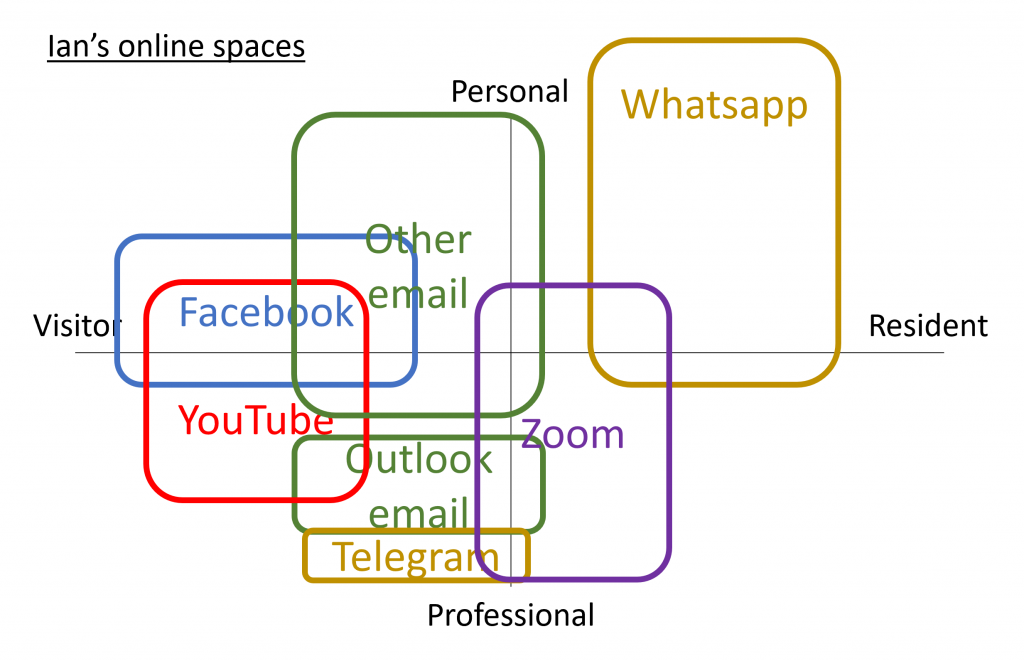

Because of these early experiences, I see online spaces primarily as tools to get something done: I’m very much a Visitor in online spaces (White & Cornu, 2011). I go online to find a piece of information, send a message to somebody or watch a video, and then disconnect to live my life in—to my mind—the “real” world offline. This probably explains why most of my boxes in Fig. 1 are squeezed towards the Visitor side of the spectrum. However, I have begun to realise that this is not how the Gen Z (and my children) see online spaces, which very much form a part of their “real” world (Buckingham, 2013), and that there are very real implications for how best to reach and teach them (McFarlane, 2019).

Fig. 1. Drawing out how I engage with online spaces made me realise, interestingly, that I consciously choose to be a Visitor, sensu White & Cornu (2011), in most cases.

Growing up with this worldview, I try to keep a strong separation between what I do online in my personal and professional lives. Whatsapp is (mostly) personal and Telegram is entirely professional. Hotmail is personal and Outlook is entirely professional. However, sometimes the lines are blurred due to necessity: I have 2 work groups on Whatsapp because the other users don’t use Telegram, and I had to use my Gmail account for some professional situations (I actually tried creating a new Gmail account for purely professional purposes but that was blocked by Google for some reason). I am, however, not fearful of trying to figure out how things work—having had to troubleshoot internet connections and office photocopier machines by navigating through unfathomable computer jargon in the “old days”, instead of simply pressing a “Troubleshoot” as I most often encounter today.

I’m hoping that ONL may change my perspective on things and help me become more comfortable with being a Resident in some online spaces, and learning how to set limits and boundaries on what I want to share with others. So far, the first webinar by David White was an eye-opening paradigm shift on how people participate in online spaces and provides a very useful framework for looking at things (White & Cornu, 2011). My interactions with my Problem-Based Learning group have also been very interesting. The discussions so far have brought to my attention a wide diversity of views and experiences that would otherwise have remained invisible to my mental eye. I look forward to learning more from the others and to contribute my own views to the group.

References

Buckingham, D. (2013). Making sense of the ‘Digital Generation’: Growing up with digital media. Self & Society, 40(3), 7-15.

McFarlane, A. (2019). Growing up digital: What do we really need to know about educating the digital generation. Nuffield Foundation.

White, D. S., & Le Cornu, A. (2011). Visitors and Residents: A new typology for online engagement. First monday.