Learning in Communities – networked collaborative learning

We are more than halfway through ONL211.

PBL6 ran into stormy waters. Emotions were high as we navigated different time zones, cultural differences and personalities in the vast sea of learning in communities and networks. One recurring theme in our voyage has been what to focus on as the topics are broad and we hail from different industries and professions with rich perspectives.

Stormy seas

Stormy seas

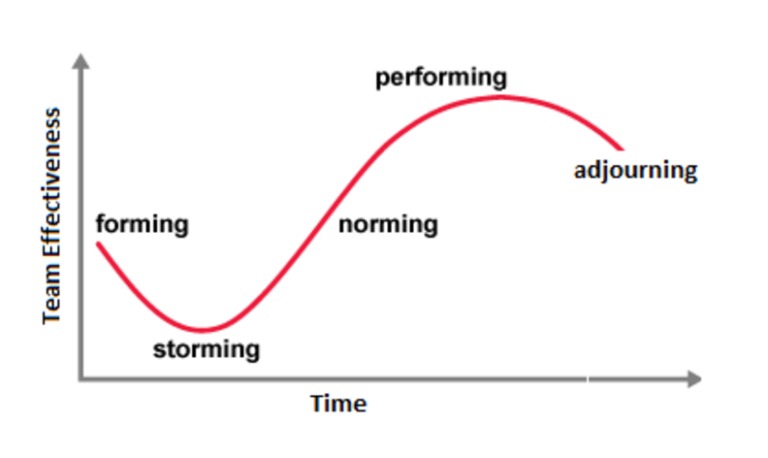

The learning came alive for me, even as Filip, our facilitator mentioned the forming–storming–norming–performing model of group development, first proposed by Bruce Tuckman in 1965. In 1977, this model expanded to include a fifth stage called adjourning that involves completing the task and breaking up the team.

Tuckman’s stages of group development

Tuckman’s stages of group development

The storming stage made way for norming, via our whatsapp chat and our zoom webinars. We were to focus on the question “How do we engage students who are not team players in the collaborative learning process?” We united to record our individual video clips which would be stitched together for our group presentation. This must be the performing stage!

Joseph brought up competition in our first discussion. This intrigued me. How do we as teachers manage competitiveness in a collaborative learning environment? Was this a polarity? A see saw between individual and team performance and excellence. In the workplace, organizations grapple with how to drive behaviour and reward employee performance on an individual and group basis.

Collaboration and teamwork are considered core competencies in the health professions. In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) and its partners recognized interprofessional collaboration in education and practice as an innovative strategy that would play an important role in mitigating the global health workforce crisis.

Now, in the throes of a pandemic, faced with healthcare staff shortages and inadequate resources, these competencies or lack of them can make or break ethically difficult situations, where there are no easy answers.

The health professions have tended to portray collaboration and teamwork in positive terms like cooperation, synergy, harmony, and altruism, with little attention given to their veiled features like competition and conflict.

Conflict is viewed negatively in the health professions as being disruptive, inefficient, unprofessional and a potential source of error that can impact patient safety. Consequently, healthcare professionals prefer to avoid conflict or resolve it quickly. When conflict bubbles to the surface, healthcare professionals tend to address it as a symptom to be treated and got rid of rather than trying to understand its root causes and mining it for its creative potential.

Eichbaum discusses how this neglect in health professions to appreciate conflict’s positive attributes is driven by (1) individuals’ fears about being negatively perceived and the potential negative consequences in an organization of being implicated in conflict, (2) constrained views and approaches to professionalism and to evaluation and assessment, and (3) lingering autocracies and hierarchies of power that view conflict as a disruptive threat.

Engeström, a Finnish sociologist, argued that teams are no longer stable entities but have become akin to knots that are “formed, dissolved … and reformed.” This perspective allows for a fluidity that we see in healthcare where teams form and disband, some quickly within days.

Korean knots, known as maedup, is a traditional Korean handicraft. Korean knotting uses a unique braiding technique. It is derived from the ancient practice of using knots for practical purposes; e.g. in fishing nets, agricultural tools, stone knives and axes. Today, modern Korean artists use the traditional knots in their works, such as accessories, jewelry and home interior decorations.

Korean knots, known as maedup, is a traditional Korean handicraft. Korean knotting uses a unique braiding technique. It is derived from the ancient practice of using knots for practical purposes; e.g. in fishing nets, agricultural tools, stone knives and axes. Today, modern Korean artists use the traditional knots in their works, such as accessories, jewelry and home interior decorations.

“Knotworking” refers to partially improvised but intense forms of collaboration between partners who despite being otherwise only loosely connected engage in rapidly solving problems and designing solutions when their common objective so requires.

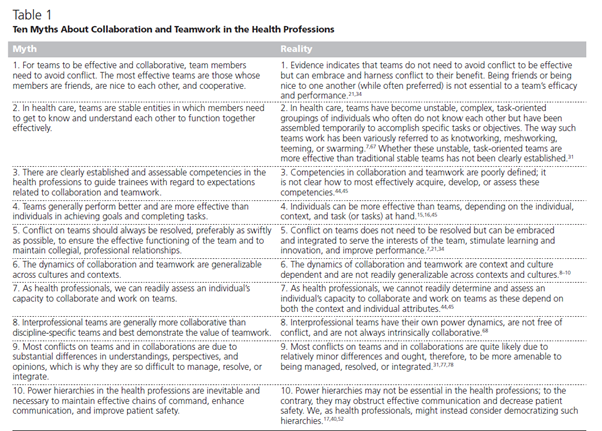

How are collaboration and teamwork interpreted, contextualised and evaluated? The following shed light on different perspectives.

The concept of teams obscures, rather than reveals, the real relationship challenges our organizations face. Teams are a fiction, a verbal convenience, rather than a useful description of how people in a firm cooperate and collaborate to create value.

Many people act as if being a team player is the ultimate measure of one’s worth, which it clearly is not. There are many things individuals can do better on their own, and they should not be penalized for it.

One myth about teams is that, to be successful, everyone must be friends. Research says it’s the other way round: team performance drives the quality of relationships. When teams fail, this poor performance upsets their members who then take out their frustration on one another.

What have I learnt reflecting on PBL6’s experiences?

It is crucial to make space for conflict and dissent on teams. This will promote handoff of important information and improve group decision making and performance. Lencioni talks about trust being a vital quality for teams to develop to engage in constructive dissent and embrace conflict. We, as team members want our individual participation to be recognized and our opinions heard and considered.

What strategies are in place for integrating conflict to move teams in the health professions from good to great? Eichbaum proposes three approaches. These are listed below.

- Cultivating psychological safety to make space for interpersonal risk-taking without undue fear of the negative consequences of conflict;

- Viewing conflict as a source of expansive learning and innovation (through models such as Activity Theory, which offers a workplace theory that views conflict as a resource for learning and innovation rather than as a problem to be solved);

- Democratizing hierarchies of power through education in the humanities, which provide the imaginative conditions for the tolerance of ambiguity and uncertainty, and ideally by advancing the humanities to the core of the curriculum.

Collaboration and Teamwork in the Health Professions: Rethinking the Role of Conflict

Collaboration and Teamwork in the Health Professions: Rethinking the Role of Conflict

Quentin Eichbaum, Acad Med. 2018;93:574–580.

There is hope of improving patient care, if we individually and corporately, integrate conflict’s inevitability and its innovative potential and incorporate it into collaboration and teamwork, in the health professions.