For good pedagogical reasons, the ONL222 course is a forum which welcomes, fosters, and practices openness. Higher education institutions increasingly often emphasize the benefits of openness[1], with digital open resources and practices contributing to an increasing range of pedagogical possibilities. Generally, following Bali et al.’s (2020) understanding of different forms of openness, it is important for educators to make informed decisions depending on the pedagogical philosophy, structure, and design of courses. As Cronin (2017) rightly states, open education is a complex organism, which is influenced by contextual and personal factors. Undoubtedly, the sharing of open educational resources (OER) and open educational practices (OEP) may positively add quality to education and learning at all levels. However, Cronin (2017) also identified in her research that many educators are challenged to find the right balance between privacy and openness, at individual and policy level. In addition, it is important to remember that education, particularly at higher tertiary level, is subject to continuous change. Due to the technological development and growing range of useful tools for open learning, educators and learners need to constantly re-negotiate their own views and be able to identify most relevant content in an exponentially growing market of open opportunities. Bali et al. (2020) provide relevant guidance by distinguishing between open educational resources (OER) with focus on content, and open educational practices (OEP) with focus on learning as a process.

Apart from evident benefits, such as related to better accessibility of OER and a greater potential of learning opportunities through OEP, the increasingly complex higher education environments may pose cognitive and mental challenges for individual learners and educators alike. Open learning, and learning in general, is indeed a process for everyone involved.

One of the key issues of learning in the digital age with its exponential growth in knowledge is that the cognitive capacities of individual educators and learners remain limited. Being exposed to an increasingly growing, infinite number of resources and unlimited potential, educators and students may increasingly experience cognitive challenges and stress. While acknowledging the benefits of the digital age and useful open resources, the infinite space of online educational possibilities may feel overwhelming. Apart from a possible sensation of drowning in a flood or overflow of information, proactive openness requires informed decision making regarding the chosen tools and includes the risk of public scrutiny and exposure to criticism.[2]

Educators and learners need guidance and orientation to manage the exponentially increasing amount of information and possibilities available in our digital age. This is probably also a key reason why we cannot expect fast changes in learners’ intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and overall attitudes towards and expectations of learning. A recent study by Valtonen et al. (2022) confirms that the use of new technology for learning and research purposes does not cause fast changes, but that any such development evolves rather slowly. While open education undoubtedly provides access to very valuable resources, educators first need to orient themselves, keep up to date with current research and pedagogical trends, and function as facilitators, maybe even as gatekeepers, to help learners find orientation in the myriad of online resources and opportunities.

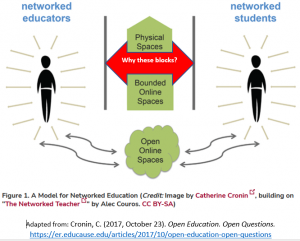

Generally, it is important to acknowledge that all modes of learning provide benefits in their own way. However, the model for networked education (Figure 1 below) by Cronin (2017) seems to promote online education as a better, pedagogically more valuable mode in comparison to blended learning, particularly as opposed to traditional face-to-face contact classes.[3] Considering pedagogical practices, Figure 1 is misleading as the blocking bars suggest minimal to no interaction between educators and learners in physical (actually rather blended) mode, and bounded online spaces. This flaw in Cronin’s assumption becomes particularly noticeable if we compare massive open online courses (MOOCs) with classic contact/blended courses.

Regardless of the teaching mode, learning is subject to change, also in physical and bounded online spaces in which focus is rather on blended and flipped learning, which emphasize the value of collaborative learning (Valtonen et al., 2022)[4]. Particularly collaboration in small teams can provide meaningful professional and psychological support for educators and learners. In the context of massive open online courses, a major challenge is caused by the unfortunate teacher-learner ratio and reduced learner-centredness, to the disadvantage of learners. On this note, the teacher-student ratio should be taken carefully into account, to maintain high-quality teaching, learner-centred support, and to offer empowering and valuable learning experiences. Constructive teacher-learner interaction, peer support and collaboration in small groups are particularly important in courses which require argumentation, analytical and critical thinking, and overall, a meaningful exchange of ideas and intellectual input.

Overall, the boundaries between different learning modes have to some extent become blurred, and on a positive note, open digital resources and educational technologies will most likely be used in all modes of learning. Naturally, we should embrace the potential of technological innovations in pedagogy, as these have enabled new possibilities to support teaching and learning practices (Valtonen et al., 2022). Learning will most likely happen in blended form, in open online as well as closed physical spaces, yet with the digital possibilities and open learning resources constantly being available. Generally, the modes of learning do not exclude each other, they rather complement each other, and most likely serve a useful purpose, depending on the pedagogical context, purpose, and learning outcomes. Eventually, there is a time for all modes of learning, and ideally we embrace the added possibilities provided through online open resources and related practices.

References

Bali, M., Cronin, C. and Jhangiani, R.S., 2020. Framing Open Educational Practices from a Social Justice Perspective. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2020(1), p.10. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jime.565

Cronin, C. (2017, October 23). Open Education. Open Questions. EDUCAUSE Review 52, no. 6. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/10/open-education-open-questions

Valtonen, T., López-Pernas, S., Saqr, M., Vartiainen, H., Sointu, E. T., Tedre, M. (2022, March). The nature and building blocks of educational technology research. Computers in Human Behavior. Volume 128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107123

[1] This can be even noticed in the architecture of modern or refurbished university buildings and seminar rooms, many of which are built fish-bowl style, with massive glass walls. Modern architecture deliberately communicates openness in an educational context.

[2] In research conducted by Cronin (2017), respondents admitted that practicing open education was very time consuming and required careful reflection, even if only posting one message or tweet. While Cronin does not expressively state that this was due to potential public criticism, I assume that educators feel greater pressure to perform particularly well in open digital forums. After all, what goes online stays online, and even short tweets contribute to the perception of digital identity.

[3] Nevertheless, Cronin (2017) also admits that this is a highly simplified model, and that openness is a highly complex concept.

[4] Valtonen et al. (2017) have identified an increasing focus on collaborative learning approaches in all modes, including blended, flipped, and distance learning.